Finding expected values of random variables in R

Today, I answered a StackOverflow question where the author was implementing a function for finding the mean of a continuous random variable, given its probability density function (PDF).

In the process of writing up my answer, I ended up applying some functional programming techniques (specifically function factories). I also found myself exploring the problem quite far outside the scope of the original question, so I thought the full story would make more sense as a blog post – so here we are!

We’ll be going through a simple R implementation for finding the expected value for any transformation of a random variable.

Some maths

(Feel free to skip ahead if you’re allergic to maths! It’s not long though.)

Expected values

I’m going to assume that you are already familiar with the concepts of random variables and probability density functions, so I’m not going to go over them here. However, as expected values are at the core of this post, I think it’s worth refreshing the mathematical definition of an expected value.

Let \(X\) be a continuous random variable with a probability density function \(f_X: S \to \mathbb{R}\) where \(S \subseteq \mathbb{R}\). Now, the expected value of \(X\) is defined as:

\[ \mathbb{E}(X) = \int_S x f_X(x) dx. \] For a transformation of \(X\) given by the function \(g\) this generalises to:

\[ \mathbb{E}(g(X)) = \int_S g(x) f_X(x) dx. \]

They key point here is that finding expected values involves integrating the PDF of the random variable, scaled in some way.

Moments

Moments in maths are defined with a strikingly similar formula to that of expected values of transformations of random variables. The \(n\)th moment of a real-valued function \(f\) about point \(c\) is given by:

\[ \int_\mathbb{R} (x - c)^n f(x) dx. \]

In fact, moments are especially useful in the context of random variables: recalling that \(\text{Var}(X) = \mathbb{E}((X-\mu)^2)\)1, it’s easy to see that the mean \(\mu\) and variance \(\sigma^2\) of a random variable \(X\) are given by the first moment and the second central moment2 of its PDF \(f_X\). That is:

\[ \mu = \int_\mathbb{R} (x - 0)^1 f_X(x) dx, \] and \[ \sigma^2 = \int_\mathbb{R} (x - \mu)^2 f_X(x) dx. \]

Other properties of distributions (such as skewness) can also be defined with moments, but they’re not that interesting, really. You can read up on that, though, if you’re into that sort of thing.

Finding expected values

Analytically

Yes, this can, of course, be done! (For many distributions at least.) But that’s not what we’re here for today. So let’s just… move right along, in an orderly fashion.

Numerically

Like we covered in the maths bit, finding expected values involves finding values of definite integrals. That means that the problem can be solved computationally with the use of numerical integration methods.

Numerical integration

We could write our own function to do just that. In R, a bare-bones implementation of numerical integration would look something like this:

integrate_numerically <- function(f, a, b, n = 20) {

dx <- (b - a) / n

x <- seq(a, b - dx, dx)

sum(f(x) * dx)

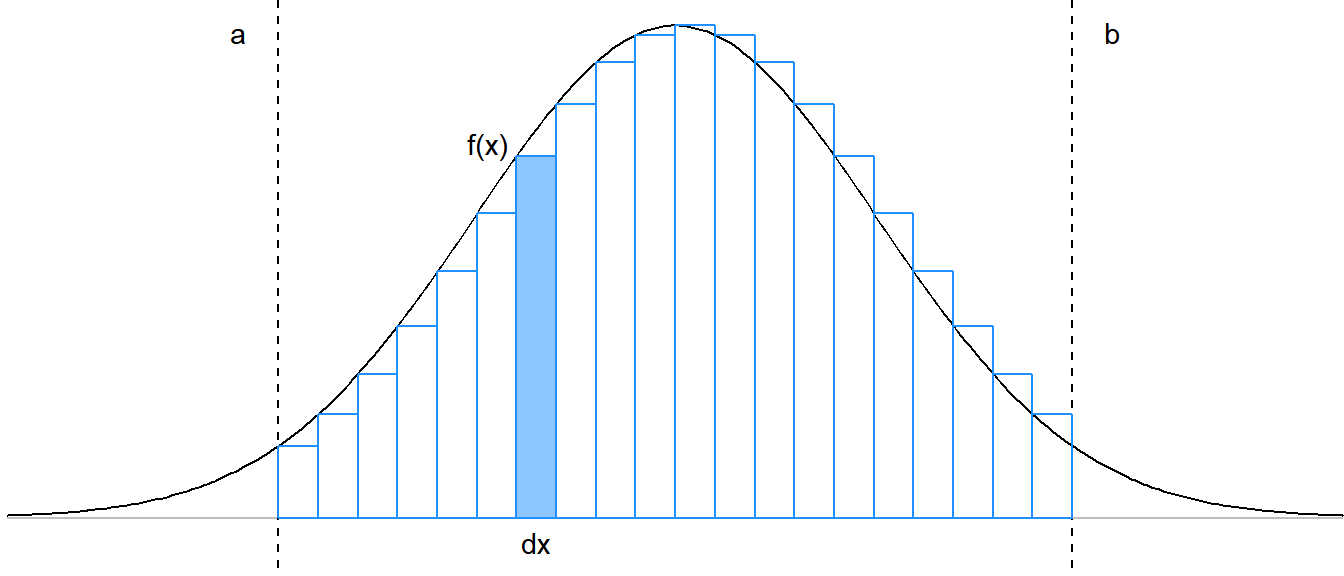

}This function finds the area under a curve \(f\), between points \(a\) and \(b\), by splitting the interval \([a,b]\) into \(n\) smaller “sub-intervals”, and then approximating the area in each sub-interval with the area of a rectangle.

For each sub-interval, the approximating rectangle has width equal to the width of the sub-interval, or “\(dx\)”, and height equal to the value of the function \(f\) evaluated at the starting point of the sub-interval.

Here’s a quick diagram3 to illustrate:

integrate_numerically(dnorm, -1.96, 1.96)## [1] 0.9492712Fortunately we don’t have to be content with that. Since numerical integration is an important computational tool that comes up in many applications, smarter people already thought about it more carefully, and implemented the integrate function. (It does numerical integration too, but better.) Our implementation isn’t awful for this specific problem, but it could be a lot more efficient.

integrate(dnorm, -1.96, 1.96)## 0.9500042 with absolute error < 1e-11Expected values with numerical integration

Well, we eventually made it here! The point that we’ve been slowly approaching here is: that based on the formulae presented earlier in the maths bit, we can use integrate to find the expected value of a random variable, or a transformation of one, given its PDF. Here’s how:

integrate(function(x) x * dnorm(x, mean = 5), -Inf, Inf)## 5 with absolute error < 6e-05We could wrap this in a function for finding the mean:

find_mean <- function(f, ..., from = -Inf, to = Inf) {

integrate(function(x) x * f(x, ...), from, to)

}And then try it out with some simple distributions:

find_mean(dexp, rate = 2)## 0.5 with absolute error < 8.6e-06But it could also be useful to generalise a bit, and create a function factory instead. That would be a good way to avoid duplicating code if we wanted to find other moments, or indeed expected values of transformations. The idea is to make a function that, given a transformation function, will return another function that finds the expected value of that transformation of a random variable:

ev_finder <- function(transform = identity) {

function(f, ..., from = -Inf, to = Inf) {

integrate(function(x) transform(x) * f(x, ...), from, to)

}

}Since we know that finding moments of PDFs can be seen as a special case of expected values of transformations, we can wrap ev_finder here to define another function factory, this time for easy generation of functions to find moments.

moment_finder <- function(n, c = 0) {

ev_finder(function(x) (x - c) ^ n)

}Then, using moment_finder, we could define find_mean from before with one line. But moment_finder also makes it simple to define a function to find the variance (i.e. the second central moment):

find_mean <- moment_finder(1)

find_variance <- function(f, ...) {

mu <- find_mean(f, ...)$value

moment_finder(2, mu)(f, ...)

}And again, we can try it out on some distributions:

find_variance(dnorm, mean = 2, sd = 2)## 4 with absolute error < 2.5e-06find_variance(dexp, rate = 1 / 4)## 16 with absolute error < 0.00051There we go! Expected values for random variables and transformations – sorted.

Or are they…

Now to be clear, this implementation of finding expected values isn’t perfect. To be honest, it’s actually kind of rubbish. Among other issues, it fails quite quickly with even slightly larger means4:

find_mean(dnorm, mean = 20)## 1.148684e-05 with absolute error < 2.1e-05So, it’s clear that we won’t be using this exact implementation of this method for any serious applications. But I think the process illustrates the benefits of function factories for generalisations quite well. And I had a lot of fun writing this post!

So given \(g\) such that \(g(x) = (x - \mu)^2\) we can write \(\text{Var}(X)\) as the expected value of a transformed \(X\): \(\text{Var}(X) = \mathbb{E}(g(X))\)↩

Moments where \(c = \mathbb{E}(X)\) are called central moments.↩

If you want to see the R code I used to create this plot, check out the R Markdown source document for this post on GitHub!↩

Actually, the issue seems to pop up when the mean and variance are too far apart, as

find_mean(dnorm, mean = 20, sd = 2)works fine.↩